Update (Jan 7, 2026)

After this post was written (and last updated) on Jan 5, 2026, Erdős problem #728 saw a significant new development. The original statement was ambiguous and admits trivial solutions. After discussion on the erdosproblems forum, the consensus was that the intended formulation should require $a, b \le (1 - \varepsilon) n$ (to rule out the trivial cases) and take $C$ to be arbitrarily large. With the statement clarified, Kevin Barreto proved the conjecture by prompting ChatGPT-5.2 and then formalized the proof in Lean using Aristotle. Compared to the cases discussed below, this is the clearest evidence so far that an AI may have generated a genuinely new solution to an open Erdős problem with relatively limited human involvement (though the corrected statement had been open for only about a day).

This does not change the main point of this post: most earlier claims that "AI solved an Erdős problem" still reduce to rediscovery of known results, clarification of ambiguous statements, or verification and formalization of ideas supplied by humans.

TL;DR

As of Jan 5, 2026, no AI system has independently and completely solved a genuinely open Erdős problem. That said, AI has already made meaningful contributions and is actively accelerating progress on several Erdős problems.

Background

The prominent Hungarian mathematician Paul Erdős posed an enormous number of interesting mathematical problems throughout his life, some by himself and some with collaborators. These problems span a wide range of difficulty, and have attracted a lot of interest. Today, as AI has grown increasingly capable at mathematical reasoning, people have started using AI to tackle open Erdős problems.

In late 2025, several startups, individuals, and social-media accounts claimed that AI tools had independently solved open Erdős conjectures. These claims include problems #367, #124, #481, #333, and #897 on erdosproblems.com. Below I use a few case studies to clarify what actually happened, what role AI really played, and how far we still are from "AI independently proving frontier mathematics."

Case Studies

#367 (Media post) (LinkedIn post)

The Problem

Define $B_2(n) = \prod_{p^\alpha \,\Vert\, n,\, \alpha\ge 2} p^\alpha$, i.e., take the prime factorization of $n$ and delete the prime factors that occur only to the first power; multiply what remains. Erdős and Graham suggested in [1, pp. 68–69] that one can perhaps show $$\prod_{m< n \le m+k} B_2(n) < c_k m^2,$$ but they could not even rule out a very extreme scenario where there are infinitely many $m$ such that $$\prod_{m< n \le m+k} B_2(n) = c_k \prod_{i=1}^k (m+i-1).$$ They further believed the following is very likely true: for every $k$ and every $\varepsilon>0$, $$\prod_{m< n \le m+k} B_2(n) < m^{2+\varepsilon}.$$

The Progress

Independent researcher Wouter van Doorn proposed a Pell-equation-based construction in the comments on the erdosproblems forum, outlining a way to refute the "Perhaps" statement but leaving gaps ("I am sure someone here is able to verify..."). Terence Tao then used Gemini Deepthink to fill in the missing details and confirm the approach. The resulting argument was later formalized by Boris Alexeev using Aristotle. The "very likely" statement has not seen much progress yet.

The Role of AI

The AI mostly helped verify the approach. This conjecture has a "perhaps" part and a "very likely" part. For the "perhaps" part, after a human supplied a promising construction, the AI helped verify the plan and fill in technical details. The AI's contribution was to make the argument complete and rigorous.

#124 (X post) (LinkedIn post)

The Problem

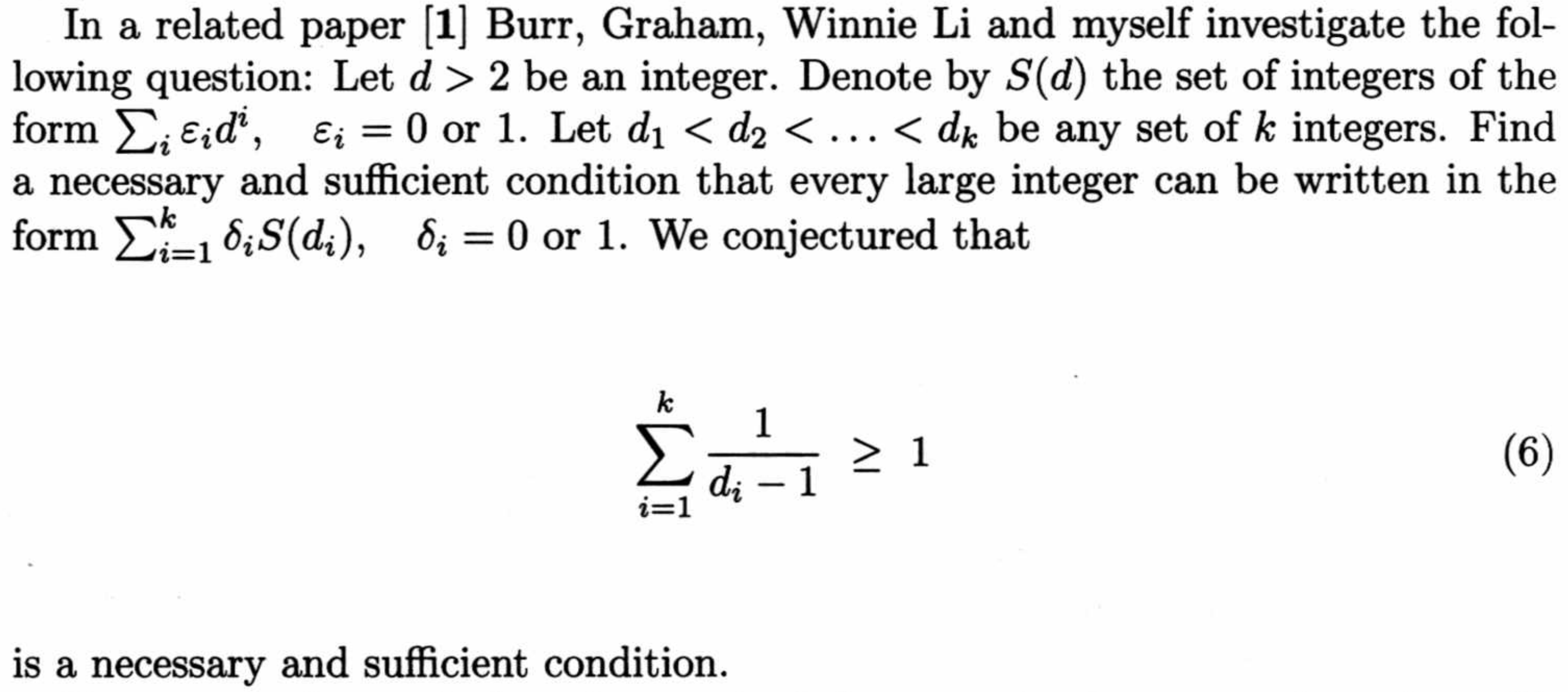

Define $P(d,k)$ to be the set of integers representable as a sum of distinct powers of $d$ of exponent at least $k$ (including $0$). Equivalently, these are the base-$d$ integers whose last $k$ digits are all $0$ and whose digits are only $0$ or $1$. The conjecture first appeared in [2, p. 133]. Erdős and three coauthors conjectured that for any integer $k\ge 1$, if $\gcd(d_1,d_2,\ldots,d_r)=1$, then every sufficiently large integer can be written as a sum of one element chosen from each $P(d_i,k)$. However, in a later single-author paper by Erdős, [3, p. 156], the problem is restated in terms of a set $S(d)$. The way it is quoted there (see the screenshot below) suppresses indices and, at least in the brief restatement, does not explicitly include the necessary coprimality condition.

As a result, it is not completely clear from the restatement whether $S(d)$ should correspond to $P(d,0)$ or $P(d,1)$. Given that the original conjecture in [2] explicitly assumes $k\ge 1$ and [3] cites it, I personally suspect that Erdős intended $S(d)=P(d,1)$ (so the later paper is the $k=1$ special case). For convenience, below we will refer to the variant that interprets $S(d)$ as $P(d,0)$ and drops the coprimality condition as the "$k=0$ variant" of the conjecture.

The Progress

Boris Alexeev used Aristotle to prove the $k=0$ variant. The original conjecture has not seen much progress so far.

The Role of AI

With all due respect to the accomplishment of formalizing/proving the $k=0$ variant, I think the main AI contribution was actually filtering out confusion about what the conjecture was even claiming. Clarifying a statement is crucial work, but it is still very different from "AI independently solved an open Erdős conjecture".

#871 (updated on 2026-01-05)

The Problem

An order-2 additive basis $A$ is a set such that every sufficiently large integer can be written as a sum of two (not necessarily distinct) elements of $A$. Let $r_A(n)$ be the number of representations of $n$ as a sum of two elements of $A$. Erdős and Nathanson proved in [4] that if there exists a constant $c > \log^{-1}(4/3)$ such that $r_A(n) \ge c \log n$ for all $n$, then $A$ can be decomposed as the union of two disjoint order-2 additive bases. They conjectured that this hypothesis could be weakened to $\lim_{n\to\infty} r_A(n) = \infty$.

The Progress

Wouter van Doorn used ChatGPT to find a later, highly relevant Erdős-Nathanson follow-up paper [5]. In [5], they construct an example with $r_A(n) \ge t$ for all $n$ and fixed $t$ that nevertheless cannot be decomposed as the union of two disjoint order-2 additive bases. While their construction does not directly address the condition $\lim_{n\to\infty} r_A(n)=\infty$, Daniel Larsen reports that his multi-agent system (built with Gemini 3 Pro and Claude Opus 4.5) found a small but nontrivial modification of the same strategy, yielding a counterexample to #871.

The Role of AI

This is a promising example of AI contributing something closer to mathematical discovery. Daniel Larsen described the process as:

Roughly speaking the process was I read the Erdős-Nathanson paper, wondered what the obstacle was in extending their construction, told my system to formalize the relevant parts of their paper, then to think about the extension, then to formalize it.

A human provided the rough idea that existing constructions might inspire a counterexample. Then, AI helped refine the idea through reasoning and formalization, ultimately producing the counterexample. In this problem, AI's contribution was more essential than in other cases. It didn't merely fill in proof details as in #367, but actually suggested how to adapt existing techniques to construct the counterexample.

#481 (X post 1) (X post 2), #333 (Reddit post), #897 (X post)

The Progress

These cases followed a similar pattern: an AI tool appeared to produce a proof "independently," and people initially took this as evidence that an open Erdős conjecture had been solved by AI. Soon after, it turned out that essentially the same proof already existed in the literature. The result had not been "open" in the intended sense; it had simply been overlooked. For more context, see Terry Tao's post.

The Role of AI

In these examples, AI's main contribution was effectively literature retrieval. This is not limited to search agents that explicitly call search tools for retrieval. Almost certainly, at least some AI companies are (legally or illegally) collecting and extracting high-quality text from the mathematical literature for training and therefore the model remembers these materials in its weights. When a similar problem is asked later, the model leverages these internalized patterns to reconstruct the solution, and this process acts as a form of implicit retrieval from the model's parametric memory.

Summary

For a more comprehensive list of how AI is contributing to Erdős problems, the community maintains a wiki page: AI contributions to Erdős problems.

The goal of this post is to fact-check claims that "AI solved an Erdős problem", and to clarify what AI has actually accomplished in these examples and where the technology currently stands.

2025 was nevertheless a remarkable year for AI for mathematics. Systems that combine language models with proof assistants progressed from struggling on relatively elementary problems to contributing meaningfully on research-level questions. This reflects advances in reinforcement learning and agentic systems, the growing maturity of Lean and mathlib, and increasing collaboration between mathematicians and AI researchers. Still, the state of the art has not reached the point where we should expect fully autonomous resolution of deep open conjectures.

Even so, I do believe that, with continued progress, we may not be very far.

References

[1] Erdős, P., & Graham, R. L. (1980). Old and new problems and results in combinatorial number theory (Vol. 28). L'Enseignement Mathématiques, Université de Genève.

[2] Burr, S. A., Erdős, P., Graham, R. L., & Li, W. W. C. (1996). Complete sequences of sets of integer powers. Acta Arithmetica, 77(2), 133-138.

[3] Erdős, P. (1997). Problems in number theory. New Zealand Journal of Mathematics, 26(2), 155-160.

[4] Erdős, P., & Nathanson, M. B. (1988). Partitions of bases into disjoint unions of bases. Journal of Number Theory, 29(1), 1-9.

[5] Erdős, P., & Nathanson, M. B. (1989). Additive bases with many representations. Acta Arithmetica, 52(4), 399-406.